Cane Creek. Caney Fork. Cane Branch. It seems every WNC community has them — place names that ring with echoes of a formerly widespread plant that holds great ecological and cultural significance here. It’s river cane, an evergreen grass that once covered hundreds of thousands of acres along the waterways of the southeastern U.S., creating a rule of thumb old-time farmers used for soil fertility. It was said that 10-foot-tall cane grew in good soil, while 30-foot-tall cane indicated the best soil around.

River cane (Arundinaria gigantea) is a bamboo species native to the Southeastern United States and technically a large grass (family Poaceae). As the name implies, river cane is found along streams and river banks, creating dense stands called canebrakes – ecological communities that excel at stabilizing streambanks, thanks to extensive root networks that help hold the soil in place, reducing sediment pollution in waterways.

Over 98% of canebrakes have disappeared due to agriculture, overgrazing, fire exclusion, and urban development.

Sediment is the number one pollutant for North Carolina waterways, with stormwater runoff being the primary source of sediment pollution. The high density of plants in a canebrake slows runoff and helps trap free-flowing sediment, acting as a filter before stormwater flows into the stream. Canebrakes provide a unique habitat for animals, including many insects, migratory birds, reptiles, and mammals such as swamp rabbits, deer, and black bears.

Sadly, despite their many benefits, over 98% of canebrakes have disappeared due to agriculture, overgrazing, fire exclusion, and urban development. The scarcity of river cane has also affected the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian (EBCI), whose artisans have used this natural resource for centuries to make beautiful woven baskets, fish traps, and arrow shafts, among other items. The dwindling stands of mature river cane cause EBCI artisans to travel further to find suitable material. Raising awareness of river cane’s ecological and cultural significance is critical in restoring river cane populations, not only for future generations to grow up with healthy streamside habitats but also for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to maintain their cultural heritage.

Let’s Identify River Cane

Native river cane is often mistaken for non-native, invasive bamboo species. Here are some key characteristics to help identify river cane.

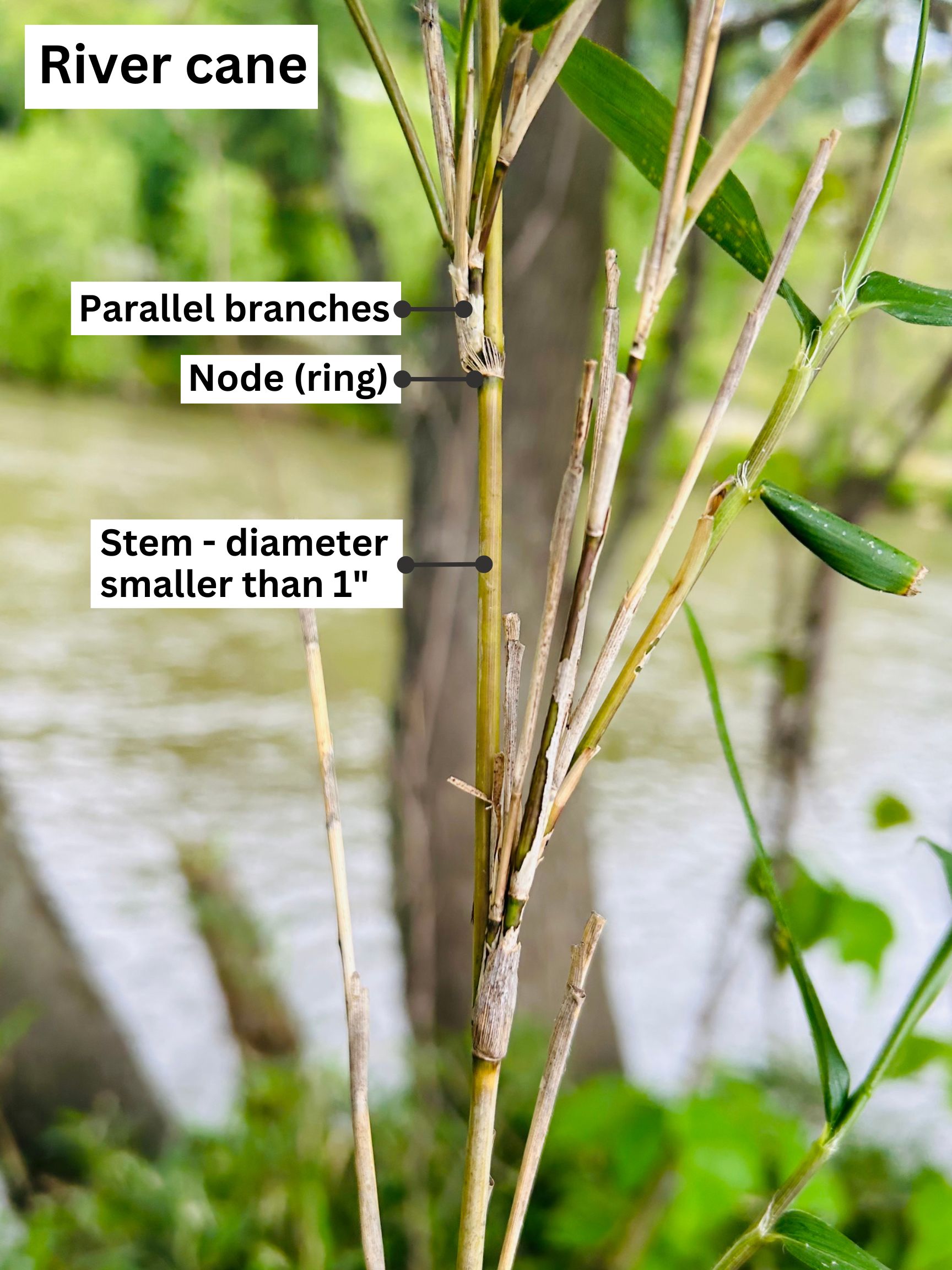

Size & Height

- River cane stems are typically less than one inch in diameter, and 6 – 15 feet tall. River cane can grow up to 25 feet, but the slower-growing native needs decades to reach this height. In contrast, non-native bamboo grows at a much faster rate, with a stem that is typically greater than 1” in diameter and a maximum height of 30 feet.

Branching Pattern & Angle

- River cane has branches that emerge at rings along the stem. These rings are called “nodes.” Branches are added each year, with annual branches growing from the same node. The many branches at the node will appear to be tangled. Invasive bamboo branches are longer and more slender than river cane.

- River cane branches are angled parallel to the main stem. Non-native bamboo branches are typically at a 45 degree angle or perpendicular to the stem.

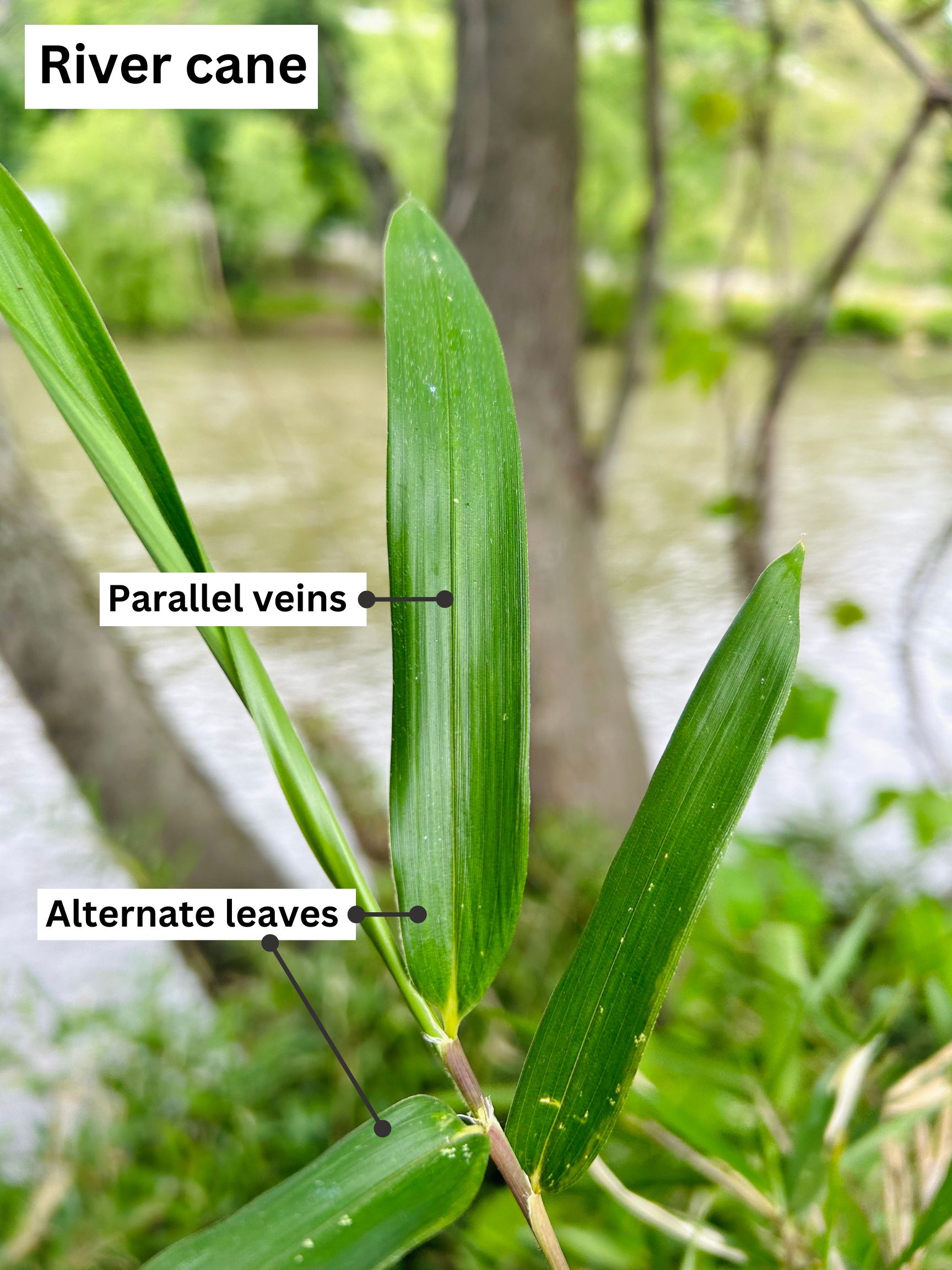

Leaves

- The leaves feel leathery and have a few hairs on the underside.

VS.